Synaesthesia is a perceptual phenomenon where stimulation of one sense triggers experiences in another sense. For example, a synaesthete might see colours when music plays, or taste flavours when they speak different words. The word synaesthesia originates from the Greek words ‘syn’ for union and ‘aesthesis’ for sensation, literally translating to ‘a union of the senses’.

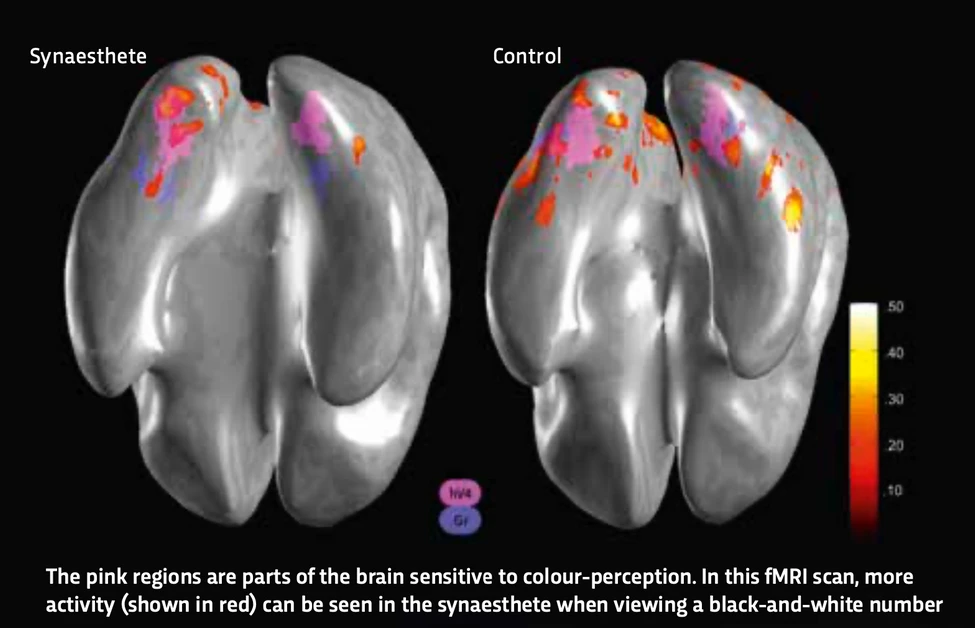

There are over 70 types of synaesthesia, which cause associations between different types of sensory input, but what they all have in common is that the associations are involuntary, present from early childhood, and remain consistent throughout life. It is thought that synaesthesia is caused by extra connectivity between sensory regions of the brain, so stimulation of one sense cross-activates the other.

In the 1990s, sound-colour synaesthetes were blindfolded and put into an fMRI scanner. They displayed activity in visual regions of the brain when sounds were played, a pattern not seen in non-synaesthetes. We now know that white matter, which connects different brain regions, is organised differently in synaesthetes’ brains, and they have more grey matter in regions responsible for perception and attention.

We are all born with many cross-connections between brain regions, but for most of us, these are pruned during early development. One theory is that synaesthetes’ brains go through less pruning, so they experience interlinked senses throughout life.

When was synaesthesia discovered?

Greek philosophers may have been the first to examine the phenomenon in the 17th Century, when they pondered whether colour was a physical property of music. However, the first documented synaesthete was Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs, an Austrian physician who wrote about his own experiences with coloured words and music in 1812.

Interest in the phenomenon faded during the 19th Century and synaesthesia wasn’t formally recognised as a neurological condition until the 1980s. Since then, researchers have begun to unravel the developmental, neurological and psychological roots of synaesthesia, but many questions remain.

What senses does synaesthesia affect?

Synaesthesia can connect any two sensory experiences you care to name (and many you can’t). Some of the most common include seeing coloured letters or numbers (grapheme-colour synaesthesia), seeing colours when you hear sounds or music (chromaesthesia), and tasting words (lexical-gustatory synaesthesia).

The exact associations vary between people — one synaesthete might describe the letter ‘t’ as red, another as blue — and they seem to be learned during childhood. For example, synaesthetes often describe letter-colour associations that match the colours of childhood toys or games.

Does synaesthesia have any benefits?

Synaesthetes are more likely to enjoy creative activities due to the richer sensory experience it gives them, and people often report channelling their unusual sensory experiences into art and music. Musicians Pharrell Williams, Mary J Blige and Lady Gaga claim to have chromaesthesia (seeing colours when listening to sounds), while physicist Richard Feynman’s grapheme-colour synaesthesia (seeing coloured letters and numbers) helped him write and remember equations.

There may be other benefits too. For example, grapheme-colour synaesthesia has been linked to improved memory and faster information processing. In children, it is associated with a larger vocabulary and higher literacy. Research shows that synaesthetes enjoy an early boost to certain cognitive abilities that are maintained throughout life; elderly synaesthetes show relatively youthful memory abilities.

Although synaesthesia is usually present from childhood, there is evidence that non-synesthetes can learn some sensory associations, and in rare cases, people have developed synaesthesia after brain injury. Some scientists think that training people to associate different senses could help protect against memory decline with age. Researchers are also investigating whether trained synaesthesia can help improve conditions such as autism, dyslexia, and ADHD.

How do I know if I have synaesthesia?

Research by Prof Jamie Ward and Prof Julia Simner at the University of Sussex has found that around 4 per cent of people experience one of the three most common types of synaesthesia. A person with lexical-gustatory synaesthesia might describe words or numbers as small droplets of taste and texture on their tongue, while people with mirror-touch synaesthesia often describe tingling, heat, or pressure sensations in their own bodies when they see a person being touched. Other synaesthetes describe visual illusions such as shapes or auras in front of them when they hear words or music. If any of this sounds familiar, you might have synaesthesia!

Synaesthesia often clusters in families, suggesting a genetic component, but it isn’t as simple as there being a single gene ‘for’ synaesthesia. Research led by Dr Simon Fisher at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in the Netherlands has identified six genetic variants associated with sound-colour synaesthesia that are involved in brain connectivity and are expressed in both the visual and auditory regions of the brain.